Scansion is a critical analytical tool in the study of poetry, allowing readers to dissect the intricate metrical patterns that underpin poetic works. This method not only reveals the rhythm and flow of a poem but also enhances our understanding of its emotional and thematic depth. By examining how poets manipulate meter, we can appreciate their craft and the effects they create on the reader. This comprehensive guide will explore the fundamentals of scansion, the significance of meter in poetry, and the techniques for effective analysis, ultimately emphasizing the importance of rhythm in shaping poetic meaning.

Understanding Meter

Definition of Meter

Meter is the structured rhythm of a poem, defined by the arrangement of stressed (´) and unstressed (˘) syllables. Each line of poetry can be categorized into specific metrical patterns, creating a musical quality that enhances the overall reading experience. The study of meter is essential for understanding how poets convey emotions, set tones, and create imagery through rhythm.

Common Metrical Feet

To analyze meter effectively, it is vital to understand the basic units of rhythm, known as metrical feet. Here are the most common knowledge types:

- Iamb (˘ ´): An unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. This is the most common foot in English poetry and often mimics natural speech. For example, in the phrase “be-FORE,” the second syllable is emphasized.

- Trochee (´ ˘): A stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable. An example is “TA-ble,” where the emphasis is on the first syllable.

- Anapest (˘ ˘ ´): Two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable, as in “in-ter-VENE.” This foot often creates a quick, flowing rhythm.

- Dactyl (´ ˘ ˘): A stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables, such as “EL-e-phant.” Dactyls can lend a galloping quality to lines.

- Spondee (´ ´): Two stressed syllables, like “DEAD END.” Spondees are less common but can be used for emphasis or to create a jarring effect.

Common Metrical Patterns

Meter can be categorized into various patterns based on the number of feet in a line:

- Iambic Pentameter: Consists of five iambs per line, making it one of the most popular forms in English poetry. A famous example is Shakespeare’s sonnets, which often follow this structure: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

- Trochaic Tetrameter: Contains four trochees per line. An example can be found in the poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “By the shores of Gitche Gumee.”

- Anapestic Tetrameter: Comprises four anapests per line, creating a lively rhythm. A well-known example is from Lord Byron’s “The Destruction of Sennacherib”: “The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold.”

- Dactylic Hexameter: Features six dactyls per line and is often used in epic poetry. An example is found in Homer’s “Iliad,” which employs this meter to create a grand, sweeping rhythm.

Techniques for Scansion

Step 1: Read Aloud

The first step in scansion is to read the poem aloud. This practice helps you grasp the natural rhythm of the language and identify stressed and unstressed syllables. Listening to the poem, either through your own voice or a recording, can reveal nuances in rhythm that might be missed when reading silently.

Step 2: Identify Syllables

Next, break down each line into its individual syllables. This process involves identifying the phonetic components of each word and marking them as stressed (´) or unstressed (˘). This step is crucial, as it sets the foundation for the subsequent analysis.

Step 3: Divide into Feet

Once you have marked the syllables, group them into metrical feet. Each foot typically consists of two or three syllables, depending on the type of meter. For instance, in a line of iambic pentameter, you would find five iambs, while a line of dactylic hexameter would consist of six dactyls.

Step 4: Analyze Patterns

After dividing the lines into feet, examine the overall pattern throughout the poem. Look for regularities and variations, such as:

- Regularity: Consistent use of a specific meter can create a sense of order and predictability, enhancing the poem’s thematic elements.

- Variation: Occasional shifts in meter can emphasize particular words or moments, adding emotional weight or tension. For example, a sudden spondee in an otherwise iambic line can draw attention to a pivotal moment in the poem.

Step 5: Consider Context

Reflect on how the metrical pattern contributes to the poem’s meaning, tone, and emotional impact. Consider how variations in meter may enhance specific themes or moments within the poem. For instance, a poem that shifts from a steady rhythm to a more erratic one might signify a change in emotional state or thematic focus.

Significance of Rhythm in Poetry

Emotional Impact

The rhythm of a poem plays a crucial role in evoking emotions and setting the tone. Different metrical patterns can create distinct emotional responses in readers. For example:

- Iambic Meter: Often associated with natural speech, this meter can create a sense of calm, order, and familiarity. It is frequently used in love poetry and reflective pieces, as it mirrors the cadences of everyday conversation.

- Anapestic Meter: The rapid, flowing rhythm of anapestic meter can convey excitement, urgency, or movement. This meter is often employed in poems that depict action or celebration, engaging the reader’s senses and emotions.

Enhancing Meaning

Metrical patterns can reinforce the meaning of a poem in various ways. For instance, a poem that predominantly uses iambic pentameter may convey a sense of stability and control, while a sudden shift to anapestic or dactylic feet can introduce tension or conflict. The interplay between regular and irregular meter can highlight themes of chaos versus order, love versus loss, or hope versus despair.

Musicality

The rhythmic quality of poetry contributes to its musicality, making it more engaging and memorable. Poets often use meter to create a sense of harmony and flow, enhancing the reader’s experience. The musicality of a poem can also influence its memorability; rhythmic patterns make lines easier to remember and recite, reinforcing the poem’s themes and messages.

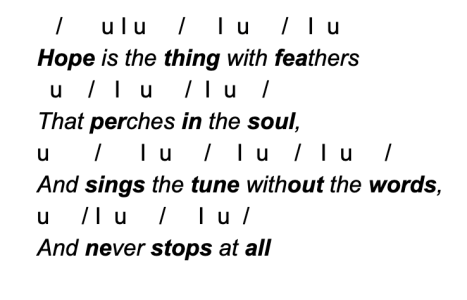

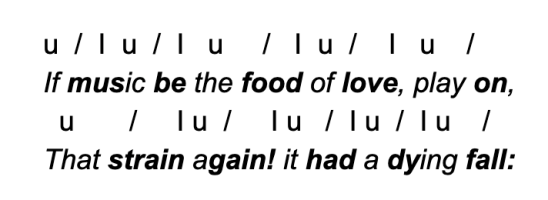

Examples of Scansion in Practice

To illustrate the concepts discussed, let’s analyze a few well-known poems through scansion.

Example 1: Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18

Text: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Scansion:

- Syllables: Shall (˘) I (´) com (˘) pare (´) thee (˘) to (´) a (˘) sum (´) mer’s (˘) day (´)?

- Feet: (˘ ´) (˘ ´) (˘ ´) (˘ ´) (˘ ´)

This line is in iambic pentameter, creating a smooth and flowing rhythm that complements the theme of beauty and nature. The regularity of the meter reflects the speaker’s confident assertion, while the iambic rhythm mirrors the natural speech patterns, making the line more relatable.

Example 2: “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Text: “Half a league, half a league, / Half a league onward,”

Scansion:

- Syllables: Half (˘) a (´) league (˘), half (´) a (˘) league (´), / Half (˘) a (´) league (˘) on (´) ward (´),

- Feet: (˘ ´) (˘ ´) / (˘ ´) (˘ ´) (˘ ´)

Here, Tennyson employs a combination of anapestic and iambic meter, creating a sense of urgency and forward momentum. The repetition of “half a league” emphasizes the soldiers’ relentless march, while the alternating meter mimics the rhythm of galloping horses, enhancing the poem’s vivid imagery and emotional intensity.

Example 3: “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost

Text: “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,”

Scansion:

- Syllables: Two (´) roads (˘) di (´) verged (˘) in (´) a (˘) yel (´) low (˘) wood (´),

- Feet: (´ ˘) (´ ˘) (´ ˘) (´ ˘)

Frost uses a mix of iambic and trochaic meter in this line, creating a reflective and contemplative tone. The slight irregularity in the meter mirrors the speaker’s internal conflict about making choices, reinforcing the poem’s central theme of decision-making and its consequences.

Conclusion

Scansion is an invaluable tool for analyzing the metrical patterns of verses, offering insights into the structure, rhythm, and emotional resonance of poetry. By understanding meter and employing effective scansion techniques, readers can deepen their appreciation of poetic works and uncover the intricacies of the poet’s craft.

The interplay of meter, rhythm, and meaning in poetry enriches the reading experience and enhances our understanding of language’s power. Whether studying classic literature or contemporary works, mastering the art of scansion will empower readers to engage more fully with the text and appreciate the beauty of poetic expression.

As we continue to explore the world of poetry, let us embrace the rhythm and music inherent in language, recognizing that scansion is not merely a technical exercise but a gateway to deeper understanding and connection with the art of poetry.

Read Also About Classic literature refers to works that have stood the test of time, resonating with generations of readers across cultures and historical periods.

Related Posts

Critical Reasoning: Bekal Penting Mahasiswa Berpikir Tajam

Critical Reasoning: Bekal Penting Mahasiswa Berpikir Tajam

Agribisnis Terpadu: Cara Mahasiswa Memahami Rantai Nilai Pertanian dari Lahan sampai Pasar dengan Lebih Realistis

Agribisnis Terpadu: Cara Mahasiswa Memahami Rantai Nilai Pertanian dari Lahan sampai Pasar dengan Lebih Realistis

Belajar Otodidak: Jalan Mandiri Menuju Pengetahuan

Belajar Otodidak: Jalan Mandiri Menuju Pengetahuan

Correctional Services: Rehabilitating Offenders in College – My Surprising Experience and Key Takeaways

Correctional Services: Rehabilitating Offenders in College – My Surprising Experience and Key Takeaways