I still remember the first poem that made me fall in love with alliteration. It was Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” with its haunting repetition of sounds—”Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary.” The way those W’s rolled off my tongue created a rhythm that stayed with me long after I closed the book. That mesmerizing musicality sparked my lifelong fascination with how repeated consonant sounds can transform ordinary language into something memorable and magical.

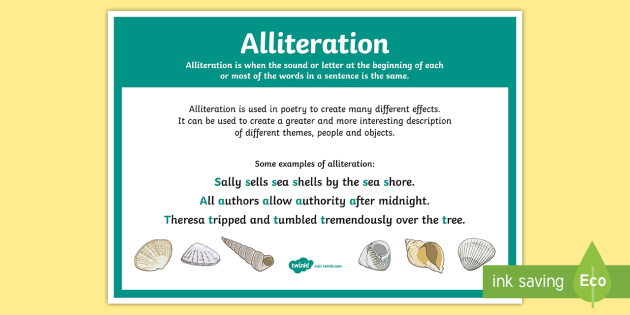

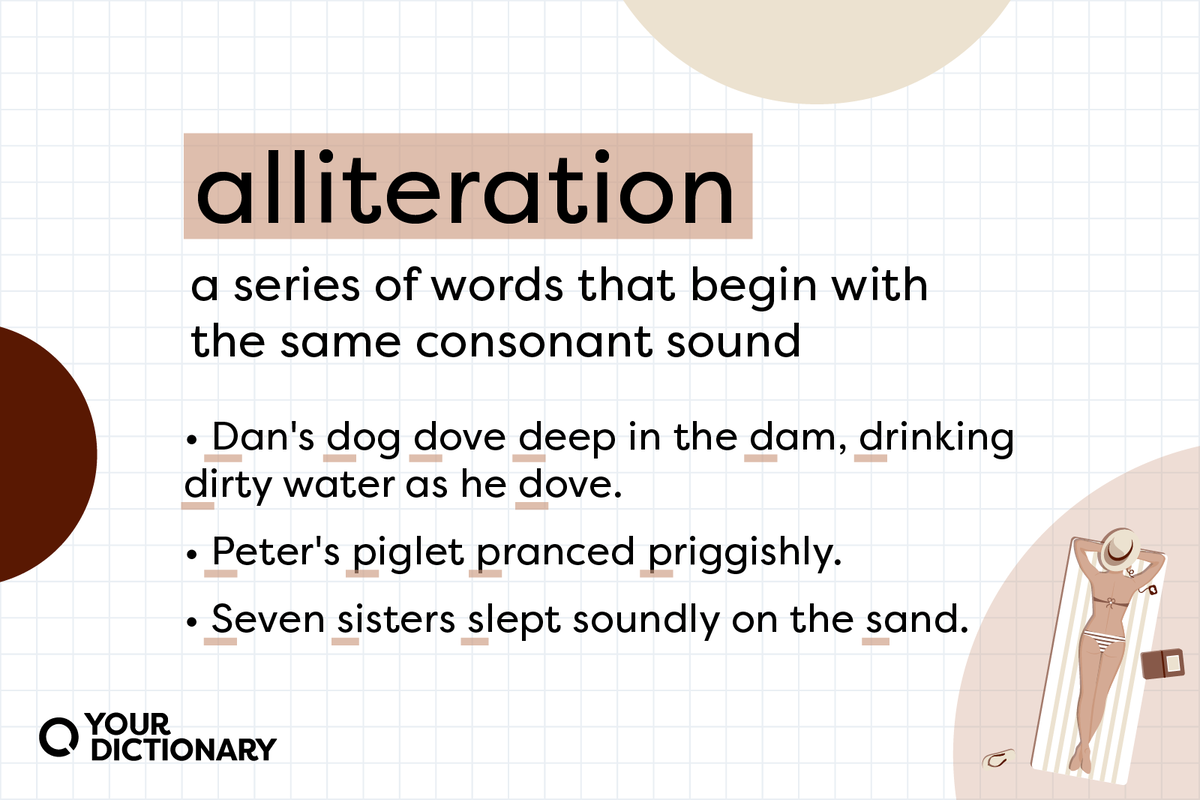

Alliteration—the repetition of consonant sounds, particularly at the beginning of words—has captivated writers and speakers for centuries. From ancient Anglo-Saxon poetry to modern marketing slogans, this literary device persists because it creates language that’s both pleasing to the ear and sticky to the memory. As someone who’s spent years playing with words professionally and personally, I’ve come to appreciate alliteration’s subtle power to elevate all forms of communication.

The Science Behind Alliteration’s Appeal

What makes alliteration so effective? According to linguistic research, our brains are naturally attuned to patterns, and the repetition of sounds creates a cognitive pleasure similar to what we experience with musical rhythms. When we encounter phrases like “wild and woolly” or “safe and sound,” our brains process them more fluently than random word combinations.

This processing fluency creates what psychologists call the “hedonic marking”—essentially, our brains find pattern recognition inherently enjoyable, which is why alliterative phrases often feel satisfying. I’ve noticed in my own writing that when I craft a particularly effective alliterative phrase, I experience a small burst of pleasure, almost like solving a puzzle.

Beyond pure enjoyment, alliteration serves practical cognitive purposes. Studies show that alliterative phrases are more memorable than non-alliterative equivalents. This explains why so many proverbs and sayings use alliteration: “look before you leap,” “time and tide,” “sink or swim.” The sound repetition creates an audio hook that helps the phrase lodge in our memory.

Alliteration Through Literary History

Alliteration’s roots run remarkably deep in literary tradition, particularly in languages with stress-timed rhythms like English.

Old English Poetry and Alliterative Verse

In Anglo-Saxon poetry, alliteration wasn’t just decorative—it was the structural foundation of verse. Old English epics like “Beowulf” didn’t rely on rhyme but instead used alliteration as the principal technique binding lines together. Each line typically contained four stressed syllables, with three of them sharing the same initial sound.

The opening lines of Beowulf demonstrate this pattern beautifully:

“Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.”

Even without understanding Old English, you can hear the deliberate repetition of consonant sounds binding these lines together.

When I first encountered Old English poetry in a college literature class, I was struck by how the alliteration created a percussive, almost drumbeat-like quality—perfectly suited for oral recitation in mead halls long before written texts were common.

Shakespeare’s Subtle Alliterations

By Shakespeare’s time, English poetry had largely shifted toward rhyme, but the Bard frequently employed alliteration for emphasis and characterization. Consider Macbeth’s famous soliloquy:

“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day…”

The repetition of “t” sounds creates a plodding rhythm that reinforces the character’s weariness with life.

In my own reading of Shakespeare, I’ve noticed he often uses alliteration to highlight moments of heightened emotion or to give certain lines a memorable quality that stands out from the surrounding text.

Modern Poetry’s Playful Patterns

Contemporary poets continue to leverage alliteration, though often with more subtlety and variation. Seamus Heaney, who translated Beowulf, frequently employed alliteration in his own verse, creating connections to ancient traditions while addressing modern themes.

Consider these lines from his poem “Digging”:

“Between my finger and my thumb The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

The soft repetition of “s” sounds creates a sense of quiet contemplation that contrasts with the potential violence suggested by the gun comparison.

Alliteration Beyond Literature

While poetry might showcase alliteration’s most artistic applications, this sound device permeates many other forms of communication.

Advertising and Brand Names

Marketers have long recognized alliteration’s mnemonic power. Think about how many famous brands and slogans use this technique:

- Coca-Cola

- Best Buy

- Dunkin’ Donuts

- PayPal

- “M&Ms melt in your mouth, not in your hands”

- “Don’t dream it. Drive it.”

Years ago, I worked briefly in advertising, and we would regularly brainstorm alliterative options for product names and taglines. The goal was always to create something that customers would remember effortlessly—and alliteration proved reliably effective for this purpose.

Headlines and Titles

Journalists and content creators frequently use alliteration in headlines to increase engagement. News outlets like the BBC or New York Times regularly employ subtle alliteration to make headlines more appealing:

- “Markets Make Modest Moves Amid Monetary Concerns”

- “Tech Titans Testify on Privacy Protections”

When I started writing professionally, an editor advised me to consider alliterative titles for articles whenever appropriate, noting that they typically garnered higher click-through rates. While I was initially skeptical, tracking my own content performance eventually confirmed this pattern.

Speeches and Rhetoric

In rhetoric, alliteration amplifies emphasis and aids memory. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches often contained masterful alliteration, such as his call for people to be judged “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Winston Churchill similarly understood alliteration’s persuasive power, as in his famous “blood, toil, tears and sweat” speech.

I’ve found that in my own presentations, strategically placed alliterative phrases often become the lines that audience members quote back to me afterward—proving their mnemonic effectiveness.

Crafting Effective Alliteration: Tips and Techniques

Creating alliteration that enhances rather than distracts requires skill and restraint. Here are techniques I’ve developed through years of practice:

Focus on Stressed Syllables

Effective alliteration doesn’t require every word to start with the same letter—it’s about the sound, not the spelling. Focus on stressed syllables for the strongest effect.

For example, in “crazy kangaroo,” both initial sounds are the hard “k” despite different spellings. Conversely, “chemistry” and “chair” don’t create true alliteration despite starting with the same letter, as their initial sounds differ significantly.

I once spent hours reworking a line in a poem until I realized I was focusing too much on letters rather than sounds. Saying potential combinations aloud helped me identify what actually created the sonic pattern I wanted.

Vary Your Approach

Alliteration doesn’t always need to occur in consecutive words. Sometimes, spacing out the repetition creates a more subtle but equally effective pattern:

“The silver swan swam silently downstream” creates a more obvious pattern than “The swan swam silently down the silver stream,” but both employ effective alliteration.

I’ve found that varying the density of alliterative sounds prevents the technique from becoming heavy-handed or sing-songy.

Consider Consonant Quality

Different consonant sounds create different emotional effects. Soft sounds like “s,” “l,” and “m” often convey smoothness or tranquility, while harder sounds like “k,” “t,” and “d” can suggest tension or abruptness.

In my poetry, I often choose specific consonants based on the mood I’m trying to evoke—sibilant S sounds for something serene or mysterious, plosive P or B sounds for more energetic or aggressive passages.

Use Alliteration Purposefully

The most effective alliteration serves content rather than drawing attention to itself. Ask yourself what purpose the sound repetition serves in your specific context:

- Does it reinforce meaning?

- Create a particular rhythm?

- Help organize information?

- Emphasize key points?

When I teach writing workshops, I encourage participants to identify the purpose of any figurative device before employing it. Alliteration used simply for its own sake often feels forced or distracting.

Avoiding Alliteration Pitfalls

While alliteration can enhance writing, it also comes with potential pitfalls:

Overuse and Forced Constructions

Perhaps the most common alliteration mistake is overuse, which can make writing feel childish or contrived. I still cringe remembering a college essay where I packed so much alliteration into every paragraph that my professor simply wrote “too much” in the margin.

Professional contexts particularly require restraint. A business report or academic paper filled with obvious alliteration may undermine credibility rather than enhancing engagement.

Sacrificing Clarity for Sound

Never compromise clarity for the sake of alliteration. If you find yourself reaching for obscure synonyms just to maintain a sound pattern, you’ve likely taken the technique too far.

I once spent far too long trying to maintain an alliterative pattern in an important email, only to realize afterward that I had selected words that didn’t precisely convey my intended meaning. The lesson was clear: content should always drive form, not vice versa.

Inappropriate Tone

Consider whether alliteration suits your context and audience. While it might enhance marketing copy or creative writing, heavy alliteration could feel out of place in formal legal documents or sensitive communications.

I learned this lesson when writing a condolence letter years ago. My initial draft included several carefully crafted alliterative phrases that, upon reflection, felt inappropriately showy for the solemn occasion. The final version was stronger for being more straightforward.

Alliteration in Different Languages

While I’ve focused primarily on English, alliteration appears across many languages, though its prevalence and function vary significantly:

German and Norse Languages

Germanic languages, like German and Swedish, share Old English’s affinity for alliteration. German poetry and proverbs frequently feature alliterative patterns, such as “Mann und Maus” (man and mouse).

Romance Languages

Languages like Spanish, French, and Italian tend to emphasize vowel sounds (assonance) more than consonant repetition. Nevertheless, alliteration still appears in proverbs and poetry, such as the Spanish “poco a poco” (little by little).

East Asian Languages

In languages like Chinese and Japanese, sound repetition functions differently due to their tonal and syllabic structures. However, many expressions in these languages contain repeated consonant sounds that serve functions similar to alliteration in English.

During my limited study of Japanese, I noticed how onomatopoeic expressions often use repeated consonant patterns to evoke specific sensations or emotions—a specialized form of sound symbolism related to alliteration.

Alliteration Exercises for Improvement

Like any literary technique, skill with alliteration improves with practice. Here are exercises I’ve found helpful:

Alliterative Journaling

Set a timer for five minutes and write continuously using words that begin with the same letter or sound. This constraint forces creative associations and helps develop comfort with alliterative thinking.

I practice this exercise regularly and find it particularly useful for breaking through writer’s block, as the focus on sound often bypasses my analytical brain and taps into more creative thinking.

Headline Transformation

Take existing headlines or titles and rewrite them using alliteration. This exercise helps develop the skill of finding alliterative alternatives without changing meaning.

When I taught a writing workshop, students transformed “Global Economic Summit Addresses Climate Concerns” into “World Leaders Wrestle with Warming Worries”—preserving the core message while adding sonic interest.

Targeted Reading

Read authors known for skillful alliteration (like Seamus Heaney, Dylan Thomas, or Sylvia Plath) with specific attention to their sound techniques. Notice how they balance obvious and subtle sound patterns.

I keep a “sound journal” where I collect particularly effective examples of alliteration and other sonic devices from my reading, which provides both inspiration and technical insight.

Final Thoughts: Alliteration as Artful Amplification

Alliteration, when artfully applied, amplifies the impact of language without announcing its presence too loudly. Like all literary devices, it works best when readers or listeners appreciate its effects without necessarily analyzing its mechanics.

My relationship with alliteration has evolved from the youthful excitement of discovering its obvious patterns in Poe and tongue twisters to a more mature appreciation of its subtle applications across all forms of communication. I no longer seek to create alliteration for its own sake, but rather welcome it as one tool among many for crafting language that resonates both intellectually and emotionally.

Whether you’re writing poetry, crafting marketing copy, or preparing a presentation, conscious use of alliteration can elevate your language. The repetition of consonant sounds connects words not just grammatically but sonically, creating patterns that please the ear and stick in the memory long after the specific content might otherwise be forgotten.

As with all powerful techniques, the key lies in purposeful application. When you deliberately deploy delightful doses of alliteration, your writing will whisper its wonders to willing witnesses—without overwhelming them with ostentatious ornamentation.