In the vast orchestra of poetic devices, assonance plays a distinct and melodious role. While more obvious techniques like rhyme and alliteration often take center stage, assonance—the repetition of vowel sounds within nearby words—creates a subtle undercurrent of musicality that can profoundly shape a poem’s emotional resonance and meaning. This repetition of internal vowel sounds, regardless of the surrounding consonants, weaves a sonic tapestry that both pleases the ear and reinforces thematic elements, making it an essential tool in the poet’s craft.

Unlike its more conspicuous cousin alliteration (the repetition of consonant sounds), assonance works beneath the surface, often registering in the reader’s mind as a pleasing harmony without drawing explicit attention to itself. It is this subtlety that gives assonance its particular power: the ability to influence the mood, pace, and emotional tenor of a poem while operating just below the threshold of conscious recognition.

From ancient oral traditions to contemporary experimental verse, assonance has maintained its significance across cultures, languages, and poetic movements. This exploration will examine how this seemingly simple device functions, its historical importance, its varied applications across different poetic traditions, and how poets continue to harness its potential to create works of lasting impact and beauty.

The Mechanics of Assonance: How It Works

Definition and Distinction

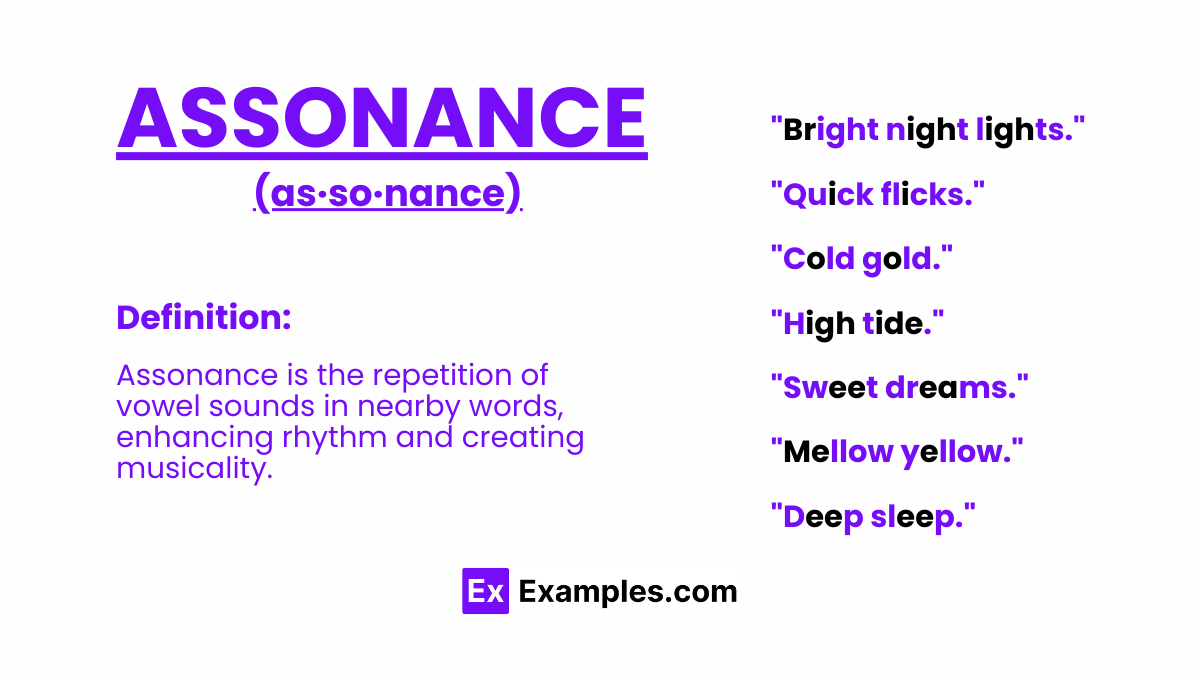

Assonance occurs when vowel sounds are repeated in close proximity, regardless of whether the surrounding consonants match. For example, in the phrase “the deep sea retreats,” the long ‘e’ sound repeats across three words, creating assonance. Importantly, assonance is based on sound rather than spelling—the words “weight” and “fade” share assonance despite their different written vowels, while “love” and “move” do not, despite their identical spelling patterns.

To distinguish assonance from other sound devices:

- Alliteration involves the repetition of consonant sounds at the beginning of words or stressed syllables (e.g., “Peter Piper picked a peck”)

- Consonance features repeated consonant sounds within or at the end of words (e.g., “tick-tock” or “blank and think”)

- Rhyme occurs when words share identical ending sounds from the last accented vowel onward (e.g., “light” and “night”)

Assonance can work independently or in concert with these other devices, creating layered sound patterns that enhance a poem’s musicality knowledge.

Phonetic Foundations

From a linguistic perspective, vowels are produced when air flows freely through the mouth without obstruction, unlike consonants which involve partial or complete blockage of the airflow. This open quality gives vowels their resonant, musical characteristics and makes them ideal vehicles for carrying emotional undertones.

English commonly recognizes five vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u) but features approximately 20 distinct vowel sounds, including:

- Short vowels: as in “bit,” “bet,” “bat,” “but,” “pot”

- Long vowels: as in “beat,” “bait,” “bite,” “boat,” “boot”

- Diphthongs: as in “boy,” “cow,” “say”

- R-controlled vowels: as in “far,” “for,” “fear”

This rich variety of vowel sounds provides poets with a nuanced palette for creating specific mood effects through assonance.

Cognitive Effects

The human brain processes repeated sounds in interesting ways that make assonance particularly effective. Studies in cognitive poetics suggest that vowel repetition creates neural patterns that:

- Enhance memorability of phrases

- Establish subliminal connections between words

- Create a sense of cohesion and unity

- Trigger emotional responses through sound symbolism

When readers encounter assonance, even if they don’t consciously identify it as such, their brains register the pattern, creating a sense of satisfaction and aesthetic pleasure similar to that experienced when listening to musical motifs.

Historical Significance: Assonance Across Time

Origins in Oral Tradition

Assonance has ancient roots in preliterate oral traditions, where it served crucial mnemonic functions. Before written language, poetic devices like assonance helped storytellers and bards remember vast epics and cultural narratives. The repeated vowel patterns created memorable sound structures that aided recall while enhancing aesthetic appeal.

In Old English poetry, such as “Beowulf,” assonance worked alongside alliteration as a primary organizational principle, creating cohesion in the absence of end rhyme. Similarly, ancient Celtic and Norse poetic traditions relied heavily on assonantal patterns to structure their verse and assist in oral transmission.

Evolution in Written Poetry

As poetry transitioned from primarily oral to written forms, assonance evolved from a mnemonic necessity to a deliberate aesthetic choice. Medieval European poetry, particularly in Romance languages, often employed assonance as an alternative to perfect rhyme. Spanish epic poetry, for instance, frequently used assonance (repeating only the vowel sounds in the final syllables) rather than full rhyme.

By the Renaissance and into the Romantic era, poets incorporated assonance with increasing sophistication, using it to create subtle emotional effects and reinforce thematic elements. As formal constraints loosened in the modern period, assonance gained even greater prominence, sometimes replacing rhyme entirely as a structural device in free verse.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives

Assonance transcends Western poetic traditions, appearing in diverse forms worldwide:

- Classical Arabic poetry features intricate assonantal patterns that complement its complex metrical systems

- Japanese poetry, including haiku and tanka forms, often employs assonance to create harmony within their brief structures

- African oral traditions use assonance extensively, particularly in praise poetry and ritual chants

- Various Indigenous poetic traditions incorporate assonance as both a practical memory aid and a means of invoking spiritual connections through sound

These cross-cultural applications demonstrate assonance’s universal appeal and utility across different linguistic contexts.

The Emotional Spectrum: How Assonance Creates Mood

Sound Symbolism

One of assonance’s most powerful effects stems from sound symbolism—the theory that certain sounds inherently suggest particular emotional qualities or physical sensations. While not universal or deterministic, certain patterns tend to emerge:

- Long ‘e’ sounds (as in “gleam” or “dream”) often evoke feelings of brightness, lightness, or elevation

- Low back vowels like ‘o’ and ‘ah’ (as in “hollow” or “somber”) frequently suggest depth, solemnity, or darkness

- The ‘oo’ sound (as in “gloom” or “doom”) can create a sense of mystery, enclosure, or foreboding

- Short ‘i’ sounds (as in “quick” or “flick”) might suggest sharpness, rapidity, or smallness

Poets intuitively leverage these associations, clustering similar vowel sounds to reinforce the emotional tenor of their work. Consider Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” where the repeated dark ‘o’ sounds in “forgotten lore” and “chamber door” establish the poem’s gloomy atmosphere before the raven ever appears.

Pacing and Rhythm

Beyond emotional coloring, assonance significantly influences a poem’s pace and rhythm. Repeated vowel sounds can:

- Accelerate tempo (often with short vowels in quick succession)

- Create a languid, drawn-out effect (typically with long vowels)

- Establish rhythmic patterns that complement or counterpoint the poem’s meter

- Create pauses or moments of emphasis when a vowel sound pattern breaks

This rhythmic function makes assonance particularly valuable in free verse, where it can provide cohesion and movement in the absence of regular metrical patterns.

Thematic Reinforcement

When skillfully deployed, assonance can subtly reinforce a poem’s thematic concerns. For example:

- Liquid, flowing vowels might underscore themes of water, continuity, or emotional fluidity

- Tight, restricted vowel sounds could emphasize confinement, precision, or tension

- Alternating patterns of light and dark vowels might reflect thematic dualities or transitions

This connection between sound and sense creates a multilayered reading experience where the poem’s sonic qualities become inseparable from its meaning.

Assonance in Action: Analysis of Notable Examples

Classical Application: Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale”

John Keats, master of sensory detail, employs assonance extensively in his odes. Consider these lines from “Ode to a Nightingale”:

“My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk”

The repeated ‘uh’ sound in “aches,” “drowsy,” and “numbness” creates a heavy, dull sensation that perfectly captures the speaker’s state of emotional torpor. This is followed by the long ‘a’ assonance in “pains” and “had,” which stretches out the line, enhancing the feeling of languid suffering.

Throughout the ode, Keats modulates between different assonantal patterns to chart the speaker’s emotional journey, from the dark vowels of the opening (corresponding to earthly suffering) to the brighter vowels when describing the nightingale’s song (suggesting transcendence).

Modernist Innovation: T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”

T.S. Eliot’s modernist masterpiece demonstrates how assonance can create coherence amid fragmentation. In the opening of “The Waste Land,” Eliot writes:

“April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.”

The repetition of the short ‘i’ sound in “is,” “breeding,” “mixing,” “memory,” “desire,” and “stirring” creates a persistent, almost irritating motif that underscores the paradoxical pain of renewal—the cruelty of hope in a desolate world. This assonantal pattern helps unify the fragmented imagery and establishes the poem’s modernist sensibility of beauty amid brokenness.

Contemporary Usage: Ocean Vuong’s Poetry

In contemporary poetry, Ocean Vuong demonstrates how assonance can serve both sonic and cultural purposes. In his poem “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong,” he writes:

“Ocean, are you listening? The most beautiful part

of your body is wherever

your mother’s shadow falls.”

The assonance of the long ‘o’ sound in “Ocean,” “most,” “your,” “body,” and “mother’s” creates a vowel echo that mimics the poem’s themes of self-address and ancestral connection. This sound pattern, with its open, resonant quality, reinforces the expansive sense of identity being explored in the poem.

Assonance in Different Poetic Forms

Formal Verse: Sonnets and Beyond

In formal verse structures like sonnets, assonance often works as a complement to end rhyme, creating internal sound echoes that enrich the poem’s acoustic texture. Shakespeare’s sonnets frequently employ assonance to create subtle connections between key words, as in Sonnet 30:

“When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past”

The repeated ‘e’ sounds in “sessions,” “sweet,” and “remembrance” create a melancholy music that enhances the sonnet’s reflective mood.

Free Verse Applications

In free verse, where traditional formal elements like meter and rhyme may be absent, assonance often assumes greater structural importance. Poets like Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg, and Mary Oliver use assonance to create cohesion and emphasis in the absence of regular patterns. Assonance helps free verse achieve what T.S. Eliot called “the ghost of some simple metre” lurking behind apparent formlessness.

Slam and Performance Poetry

In contemporary slam and performance poetry, assonance serves both aesthetic and practical purposes. The repeated vowel sounds create memorable phrases that resonate with live audiences, while also facilitating the poet’s delivery by establishing rhythmic flows that can be emphasized in performance. Poets like Andrea Gibson and Saul Williams masterfully employ assonance to create works that are as sonically powerful when heard aloud as they are meaningful on the page.

Crafting with Assonance: Techniques for Poets

Strategic Placement

Effective assonance depends not just on which vowel sounds are repeated but where they appear in the poem. Key placement strategies include:

- Positioning assonant words at the beginnings or ends of lines for emphasis

- Clustering assonance to create intense emotional effects in crucial passages

- Using isolated instances of assonance to highlight pivotal words

- Creating assonantal patterns that gradually transform as the poem progresses, mirroring thematic developments

Balancing Subtlety and Impact

The most effective assonance often operates at the threshold of awareness—present enough to influence the reading experience but subtle enough to avoid seeming contrived. Accomplished poets achieve this balance by:

- Varying the distance between assonant words

- Combining assonance with other sound devices

- Ensuring assonance serves meaning rather than mere decoration

- Allowing some assonantal patterns to emerge organically during the revision process

Revision with Sound in Mind

Many poets find that assonance emerges most effectively during revision rather than initial composition. Reading work aloud repeatedly helps identify natural assonantal patterns that can then be enhanced or modified. Some poets even create “sound maps” of their drafts, marking different vowel sounds with colored highlights to visualize the sonic architecture of their work.

Conclusion: The Continuing Resonance of Assonance

In an age of visual media and digital communication, the subtle music of assonance reminds us that poetry remains, at its core, an oral art form—one that speaks directly to our most primal responses to sound. While other poetic techniques may be more immediately apparent, assonance works at a deeper level, creating emotional resonances that often bypass intellectual analysis to affect readers directly through the ear.

The versatility of assonance—its ability to function across disparate poetic traditions, to adapt to changing formal conventions, and to accommodate different languages and cultural contexts—ensures its continuing relevance in contemporary poetry. From Shakespeare to slam poetry, from ancient oral epics to experimental verse, assonance provides poets with a tool for creating work that doesn’t merely convey meaning but embodies it through sound.

As readers and writers of poetry, cultivating an awareness of assonance enriches our experience of verse, allowing us to appreciate the subtle ways in which great poets have always known what linguists and cognitive scientists have only recently confirmed—that the music of vowels shapes not just how we hear language, but how we feel it, remember it, and find meaning within it. In the repetition of vowel sounds, we discover one of poetry’s most enduring sources of power: its ability to make language resonate beyond the page, creating echoes that linger in the mind long after the reading ends.